Central banks : the tools to fight climate change

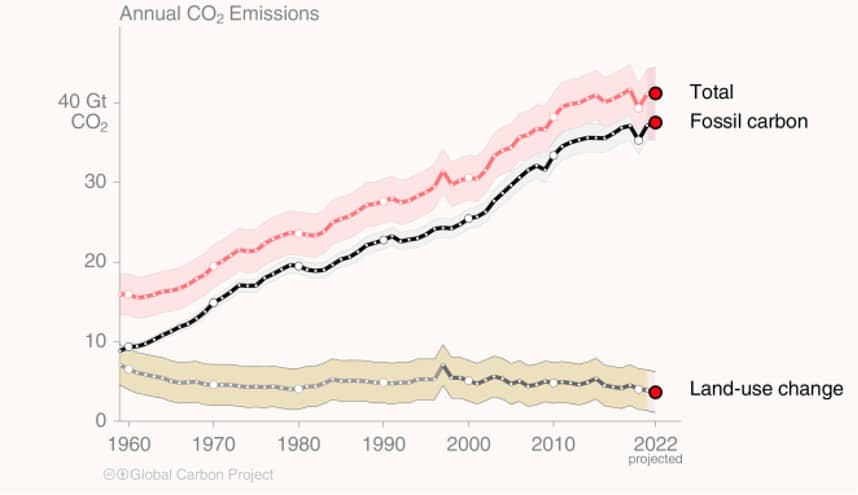

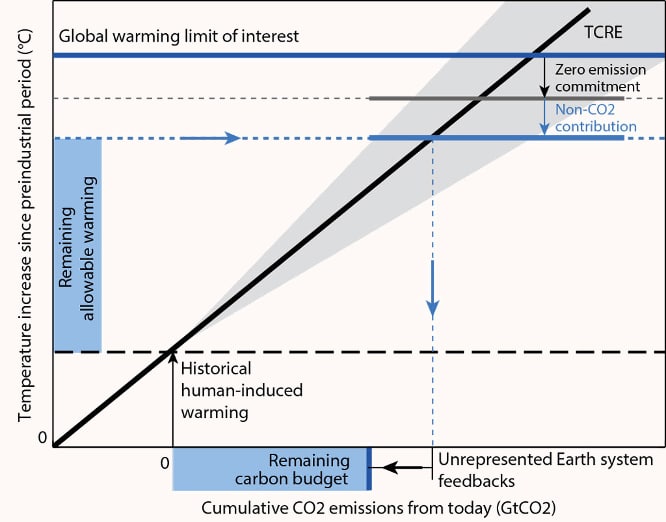

- At the current rate, the global carbon budget of 580 GtCO2 would be exhausted in less than 15 years.

- Central banks can play a crucial role in the fight against climate change, especially as it threatens financial stability and economic activity.

- In finance, climate risk includes physical risk (such as economic costs) and transition risk, which results from changes in government policies.

- In 2021, the ACPR’s stress test showed that the cost of climate-related claims would increase five or sixfold between 2020 and 2050 in some French departments.

- To integrate climate risk into financial issues, the central bank has several tools at its disposal, such as investment portfolios or prudential measures.

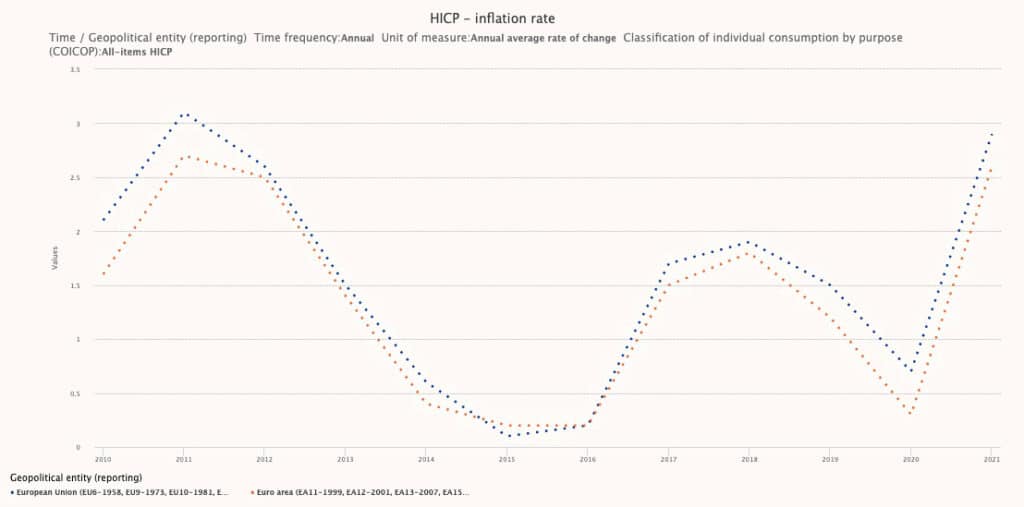

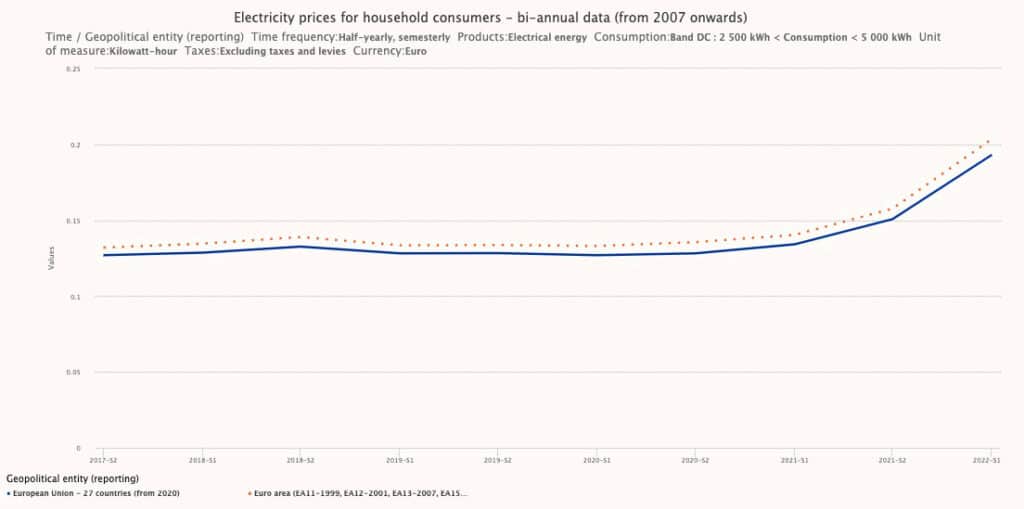

The Covid pandemic, the crisis linked to the war in Ukraine and the challenges posed by climate change present central banks with a complex challenge : to steer and control inflation that is constantly rising. The European Central Bank’s (ECB) objective is to achieve 2% inflation in the medium term – compared with 3% in Europe today – but without curbing the investments needed for the energy transition.

On the one hand, the scale of the investments required to meet climate objectives is colossal.

Our remaining global carbon budget, which represents the CO2 emissions compatible with the Paris Agreement, would be 580 GtCO2 for a 50% probability of keeping warming below 1.5°C according to the estimates of the IPCC report2. On average, annual global anthropogenic emissions are around 40GtCO2 (Global Carbon Project, 2022). At this rate, this carbon budget would be exhausted in less than 15 years. On the other hand, the sources of inflation today are multiple, from the disorganisation of value chains during the pandemic to the imbalance between supply and demand at the end of the crisis. In addition, the rise in energy prices linked to the war in Ukraine and energy transition policies are fuelling “green inflation”3.

Is it legitimate for central banks to take up the issue of combating climate change ? This question was already raised by Milton Friedman in 1970 regarding the environmental and social responsibility of companies, when he questioned the political legitimacy of company directors to provide public goods5. However, in terms of the fight against climate change, we are faced with a double failure to integrate climate risk : the failure of markets but also the failure of governments6.

Mobilisation of central banks

The expectations of economic and financial actors and regulators are legitimate. But this does not mean that central banks should replace governments.

The need for central banks to mobilise in the fight against climate change is twofold : climate change is a threat both to economic activity and to financial stability. It is therefore an integral part of the central bank’s mandate. Indeed, the TCFD report9 by the Banque de France and the ACPR in 2022 begins :

“Contributing to assessing, reducing, and managing the impact of climate risks on the real economy and the financial system is in our view an integral part of the mandate of central banks and supervisors, both in terms of monetary strategy and financial stability. The Banque de France has therefore been an early advocate for the community of central bankers and supervisors to take climate change issues into account. Internationally, it was one of the founding members of the Network of Central Banks and Supervisors for the Greening of the Financial System (NGFS)10 in 2017, which now has 121 members and for which it provides the global secretariat.”

What is climate risk in finance ?

Climate risk in finance is defined in terms of two main components : physical risk and transition risk (Carney, 2015). Physical risk represents the economic and financial costs incurred because of the increasing severity and frequency of physical climate hazards. Transition risk, on the other hand, results from changes in government policies, technological changes and changes in investor and consumer behaviour.

The transition to a low-GHG economy requires rapid and far-reaching transitions in energy, land use, urban planning, infrastructure, and industrial systems. €830 billion per year would be needed to make this transition11.

€830 billion per year would be needed to ensure the transition to a low-GHG economy.

Some sectors may lose much of their value or even disappear in the coming decades (referred to as stranded assets). Studies12 estimate that a policy to limit global warming to 2°C would mean that 35% of oil reserves, 52% of gas reserves and 88% of coal reserves would become unusable. In this context, should we then continue to invest capital in the search for and exploitation of these reserves ? These investments risk becoming unusable, very expensive, and possibly totally depreciated.

All these changes can generate losses identifiable through traditional financial risks : credit (subject-sensitive borrowers), market (asset valuation), liquidity (access to bank finance) or operational (compliance and regulatory risk).

In terms of inflation – a core mandate of the Central Bank – the physical risks of climate change lead to negative supply shocks (capital destruction, reduced labour supply, productivity uncertainties) that reduce potential output, increase output gaps and inflationary pressures. An increase in the frequency and severity of these negative supply shocks could lead to increased volatility in headline inflation and, under certain circumstances, could affect inflation expectations13.

ACPR stress tests

The ACPR (Autorité de contrôle prudentiel et de régulation), conducted a pilot climate stress test in 2021 that highlights the exposure to climate risk in France of 9 banking groups and 15 insurance groups, which together account for 85% of the total balance sheet of banks and 75% of the total balance sheet of insurers in France. This exercise shows that, for the insurance sector, the cost of climate-related claims should be multiplied by 5 or 6 between 2020 and 2050 in certain departments (particularly in the west of France).

The cost of weather-related claims should be multiplied by 5 or 6 between 2020 and 2050.

The main hazards contributing to this increase in claims are related to the risk of drought and flooding, and the increased risk of cyclonic storms in the overseas territories. If this risk were to be offset by an increase in premiums, insurance premiums would have to increase by 130 to 200% over 30 years, i.e. 3 to 3.7% per year14.

Integrating climate risk into financial issues

- To integrate climate risk into financial stability monitoring, prudential supervision and portfolio management, the central bank has several tools at its disposal (see for example the recommendations of NGFS, 201915):

- Economic and financial analysis (taking climate change into account in its models, macroeconomic projections, and risk assessment).

- Banking and insurance supervision (raising awareness and ensuring that banks and insurers manage climate risk adequately).

- Monetary policy and investment portfolios (central banks can invest in green bonds, for example).

- Prudential and financial stability measures (e.g. on capital requirements and sectoral leverage ratios).

The climate strategy of the Banque de France and the ACPR is thus embodied in all of the institution’s missions (monetary strategy, financial stability, services to the economy and society and sustainable performance). Five strategic climate actions are dedicated to priority areas : adapting monetary policy operations to climate risks, increasing the financial sector’s consideration of climate risk, assessing the integration of climate risks into company ratings, actively committing to carbon neutrality, and aiming for digital sobriety in all uses16.