The silent peril of forever chemicals

- PFAS, described as forever chemicals, are causing concern in the scientific community because of their persistent toxicity.

- A major media investigation has produced a detailed map of tens of thousands of PFAS-contaminated sites across Europe.

- Manufacturers, who have no satisfactory alternative, continue to use PFASs despite their known harmfulness.

- One of the solutions being investigated is the search for a ‘depolluting bacterium’ capable of degrading these compounds.

- The fight against PFAS requires a multidisciplinary approach, and the CNRS has set up a working group to look at their detection and decontamination, as well as alternative compounds.

- Innovating in terms of depolluting solutions will not be enough: these eternal pollutants need to be regulated.

PFAS, toxic and persistent chemical compounds, have invaded every corner of our planet. While the biological science community is mobilising to seek out micro-organisms potentially capable of degrading them, the solution goes beyond the laboratory, calling for a collective and regulatory response.

Alarming figures testify to the scale of the pollution: 1,433 ng/L at the bottom of a well in the Béarn village of Monts, 1,546 ng/L at the outlet of a borehole in La Tremblade opposite the Ile d’Oléron, 2,399 ng/Kg in hens’ eggs near the industrial basin of Pierre-Bénite south of Lyon. These readings are among the French sites most contaminated by PFASs, so-called “forever chemicals” that are of concern to the scientific community and beyond, because of their toxicity and persistence in the environment.

The acronym PFAS stands for per- and poly-fluoroalkylated substances. “These industrial chemical compounds are used in many everyday products, such as food packaging plastics and batteries,” explains Stéphane Vuilleumier, microbiologist and professor at the University of Strasbourg. They are also found in fire-fighting foams, paper production processes and textile finishing.

PFAS are everywhere

In early 2023, a consortium of major European media, including Le Monde and The Guardian, carried out an impressive investigation that produced a detailed map1 of PFAS-contaminated sites across the continent. Their work sheds light on the massive pollution of European water, sediment and soil. They listed tens of thousands of sites, including just over 2,100 « hot spots », where concentrations far exceed the thresholds deemed dangerous to health (i.e. 100 ng/L).

However, this mapping only lists sites that have been tested or identified as being particularly exposed, and only includes the best-known substances (around ten). However, the researcher points to the publication of a new nomenclature that now classifies several million different substances2 in this category, suggesting that the spread of PFAS is generally underestimated. “There isn’t a single place on Earth that doesn’t have traces of PFAS,” insists the researcher.

Despite the scientific evidence of their harmfulness “even at very low concentrations”, these substances continue to be widely produced and used by manufacturers, who have no satisfactory alternatives. Stéphane Vuilleumier points out that their deleterious effects on human health are becoming increasingly well documented, “particularly on the immune system3 and on hormones, by acting as endocrine disruptors4”.

A model of resistance to be broken

PFAS are described as forever chemicals, because they have the particularity of being made up of a carbon-fluorine bond that makes it impossible for them to biodegrade. “There are very few natural organic compounds that contain fluorine,” explains Michael Ryckelynck, a biochemist and professor at the University of Strasbourg. In 2020, this specialist in microfluidics teamed up with Stéphane Vuilleumier to find bacteria capable of breaking this bond, of defluorinating. The problem? It is estimated that over a billion different species of bacteria exist today. Finding the ideal candidate is like looking for a needle in a haystack.

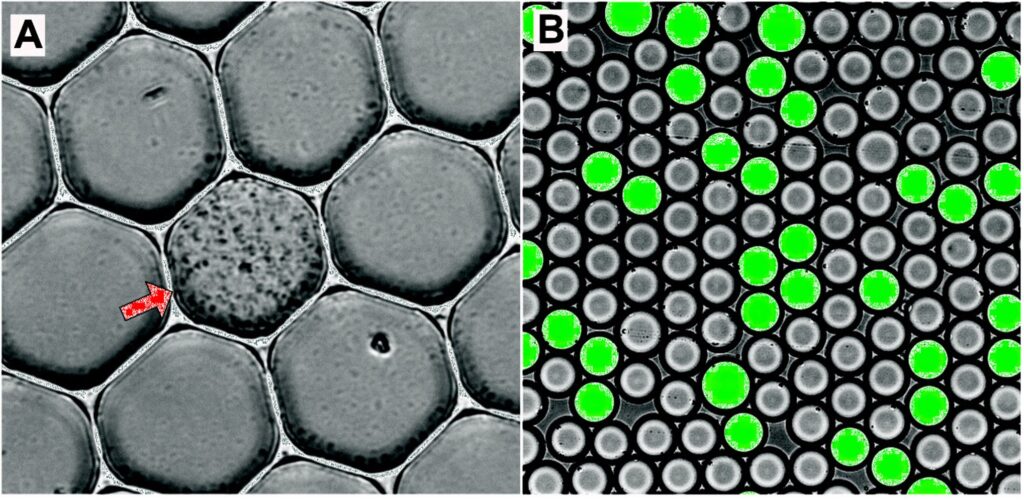

“Our expertise in microfluidics enables us to speed up tests and reactions by miniaturising them into picolitre volumes,” he explains. With this scale of experiment, researchers can analyse a very large quantity of samples in a single step. “Rather than pre-selecting candidate enzymes and bacteria and then testing them one by one, we are looking for the defluorination function in a large sample (…), at a rate of two million analyses per hour.” They have created an “analysis pipeline” in which the candidate bacteria interact with PFAS and a fluoride detector. If one of these bacteria is capable of degrading the compound, a fluoride ion is released. This will be detected by fluorescence, enabling the researchers to identify the bacteria responsible and isolate it for further study.

The fight will be collective, or not

Their initial work5 demonstrated the effectiveness of the defluoridation detector. They are now focusing on analysing environmental samples (preferably from contaminated sites) and improving the degradation properties of some of the bacteria of interest. The entire global scientific community is pursuing the same objective: to find the anti-PFAS bacterium. However, no single technology will be enough to solve the problem of PFAS. “A collaborative approach to the subject is essential if we are to succeed. We need to combine our detection method with innovations from other laboratories,” argues Michael Ryckelynck, “such as adsorption membranes6 [editor’s note: for capturing and storing PFAS], or other physical chemistry approaches for degrading these compounds.

The economic stakes for industry are titanic

This interdisciplinarity has recently taken form in France with the initiative of the Mission pour les Initiatives Transverses et Interdisciplinaires of the CNRS, with a working group7 dedicated to the detection and decontamination of PFAS, as well as to alternatives to these compounds. Chemists, physicists, biologists, engineers, sociologists, mathematicians, and others are expected to join this hotbed of science, which will aim to accelerate innovation and the emergence of concrete solutions to deal with the problem of PFAS in the best possible way.

The need for regulation

A symposium will be organised in March 2024 to bring together this wide range of disciplines and to create interaction with industry. “Industry must to be part of the equation,” insists Stéphane Vuilleumier. We need to build a relationship of trust with them. Industry is a key gateway for scientists to access soil, sediment and water samples for analysis and treatment. They also have an interest in following scientific advances closely, so that they can evaluate possible alternatives to these substances or implement pollution control prototypes.

However, the trend is not yet towards a reduction in use, stresses the researcher, “because the economic stakes for industry are titanic”. PFAS are at the heart of the global production machine: “acceleration in the manufacture of batteries for electric vehicles, for example, which requires this type of substance, will not necessarily facilitate the emergence of solutions”. However, the potential future discovery of “depolluting bacteria” must not become a pretext for continuing to pollute. For the researchers, we need to ask ourselves the right question: are we ready to do without PFASs? They are therefore calling for changes in regulations to facilitate the transition process. “Decision-makers need to carry out a benefit/risk balance between the financial impact of restricting the use of PFASs and the cost in terms of public health of their continued release into the environment.”

Whatever the outcome, the scientific community is on the move, both to innovate in terms of pollution control solutions, and to inform public decision-making and curb the threatening dispersion of these eternal pollutants.