Can beauty be quantified?

Why does there seem to be a consensus in appreciation of certain images? What underlying properties and rules determine a preference of beauty? Physicists from École Polytechnique, in collaboration with the ArtInResearch gallery, provide elements of an answer in a recent publication1 in a field at the crossroads of disciplines: “quantitative aesthetics”.

A universalist vision of beauty.

“Beautiful is what, without a concept, is liked universally.” Emmanuel Kant2

The concept of beauty, considered as a universal and intrinsic property of an object, appears in many artistic contributions, themselves rooted in all periods of history. From ancient Greece to the Renaissance, from architecture to painting, this quest for the ideal has often converged towards the establishment of precise rules of representation. These rules, sometimes very quantitative, can materialise in different ways within works of art: proportions of bodies for sculptures; act distributions and dialogue in theatre; symmetry in architectures, and many other examples. Even for contemporary works that are in line with these historical disciplines, these rules remain and constitute the first things that are taught on the academic level.

Order and chaos

“Total chaos is disquieting. Too much regularity is boring. Aesthetics is perhaps the territory in-between.” Jean- Philippe Bouchaud3

Yet, one cannot help but think of those outstanding works that present at least a sensitive transgression of these rules. How many acts and sets are there in Edmond Rostand’s Cyrano de Bergerac? What level of de-structuring is there in Picasso’s Guernica? In a way, isn’t the powerful work the one that transports us between rules and their rejection, the known and the unknown, order and chaos?

What could be more telling for researchers in statistical physics, where concepts like sudden symmetry breaking, criticality and instability are at the heart of the discipline?

Entropy as a measure of disorder.

From the point of view of physics, order and disorder are familiar notions. A magnet consists of an almost infinite number of micro-magnets, all aligned and ordered. But if the temperature is increased above the “Curie temperature”, this order is broken, the micro-magnets become independent, and the overall magnetisation is lost. The measure of this disorder and breaking of symmetry is entropy, a fundamental quantity in thermodynamics. More formally, entropy is the number of ways to organise a system so that it keeps the same physical properties. There are many ways to create disorder, but few ways to build order.

A simple experiment on visual preference

During our research, we asked the following question: is there an entropy value for classes of simple abstract images that would maximise their aesthetic qualities?

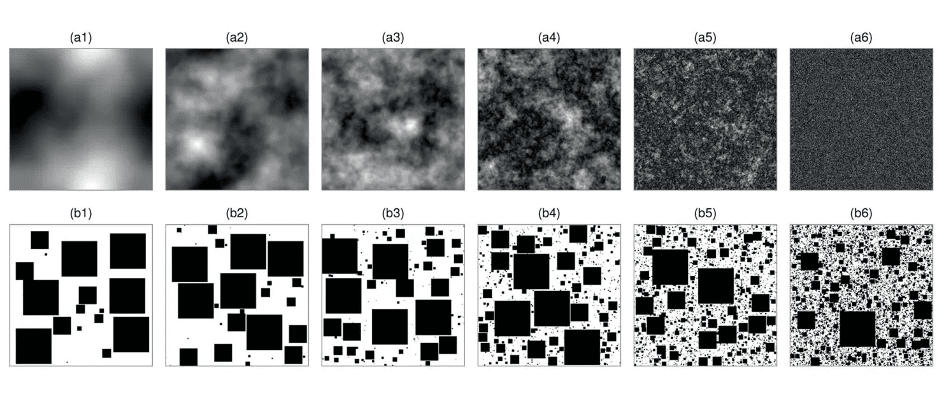

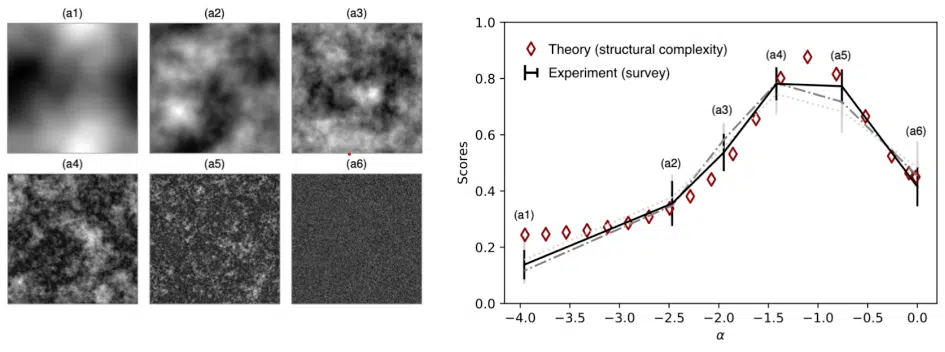

To answer this question, we first generated two classes of abstract images well distributed over three known measures of disorder: fractal dimension; algorithmic compressibility; and pattern size distribution within an image. Each of these classes of images transitions from ordered (left) to disordered (right) states. We then performed survey experiments to determine which images were most appreciated, first with the help of our colleagues (LadHyX, CFM, ENSAE), and then through adapted distribution platforms (Amazon MkTurk). In total, nearly 1000 people participated in the different experiments. The results confirmed our intuition: the images (a4,b4) obtain the best scores.

Entropy and structural complexity

Intuitively, extreme entropy values tend to bore us or lose us. Conversely, intermediate values capture our attention by maximising the presence of interesting structures – in the form of intelligible patterns that make the image unique. In a way, our brain recognises shapes and patterns while “erasing” unnecessary noise. To simulate this mechanism, we then proposed a measure of “structural complexity” (in red on graph above) highlighting these structures. In doing so, we obtained a second result: the images of intermediate entropy present, indeed, the greatest structural complexity. It should be noted that natural images, such as photographs of forests or landscapes, present an entropy (statistically condensed) around this same intermediate value.

A contribution in a growing field: quantitative aesthetics.

Today, cameras, retouching software and even search engines all benefit from recent contributions in quantitative aesthetics45. This discipline, by combining massive data banks6, image processing methods and advanced learning architectures7, has significantly improved the automatic scoring and classification of images. However, despite the performance of these tools, we can regret their inability to provide elements of understanding on the real mechanisms of appreciation. They are, in a way, automata whose rules escape us.

Our work, even if it is part of the same predictive approach, aims at putting the interpretability of the results at the centre. A fundamentally physical approach in short.