How humans will live on the Moon

- The 2024-2025 moon return programme is a long-term project: the aim is to create a space station and a lunar base that can be inhabited.

- To do this, humans must adapt to the constraints of the lunar environment: 6x weaker gravity, extreme temperatures, impromptu meteoroids, etc.

- Robotic, technological, and industrial innovation is therefore crucial to ensure human settlement on the Moon.

- This programme requires large amounts of energy, which could be provided by nuclear fission power systems.

- Humans are also returning to the Moon to mine resources such as oxygen, silicon, aluminium, iron or helium-3.

16th November 2022. The huge SLS launcher lifts off from Launch Complex 39 at the Kennedy Space Centre in Florida with the mission to send the new Orion spacecraft, developed by the US Space Agency (habitable module) and the European Space Agency (service module), around the Moon.

This mission, named Artemis I, was a great success but was only the first step in preparing for the return of humans to the Moon in 2024 (a manned Orion flyby this time) and 2025 (when a man and a woman should set foot on the Moon again).

But unlike the Apollo programme of the 1970s, this new manned return to the Moon is a long-term programme. Indeed, plans have already been made to place a lunar space station similar to the International Space Station into orbit (several modules have already been built) and to gradually set up a lunar base on the ground, which will initially be visited by astronauts on an ad hoc basis, but whose ultimate objective is to be permanently inhabited.

To implement this ambitious programme, it is necessary to adapt to the hostile environment of the Moon and to develop facilities capable of maintaining a habitable zone in what is one of the most extreme environments that humans have ever known. Let’s talk today about the technological and industrial challenges that lie ahead on the Moon in the coming decades.

A hostile environment to tame

To maintain a stable and safe habitat, you have to start by analysing the environment in which you want to settle and knowing the constraints it will place on buildings and people. As the Moon is smaller than the Earth, its mass is lower. The Moon’s gravity is six times weaker than Earth’s: all the calculations for architecture, structures and material resistance must therefore be reviewed in depth.

In addition, the Moon has a very slow rotation. There, a day lasts about two Earth weeks, as does the night. And without an atmosphere to homogenise the temperatures between the light and dark sides, temperatures vary from 120°C during the day to ‑250°C at night! Not to mention that on the Moon, meteoroids arrive intact and at full speed to the ground. Finally, we must take into account the permanent irradiation of the lunar surface by cosmic rays, a stream of particles whose excessive dose can cause burns, sterility or the appearance of cancers.

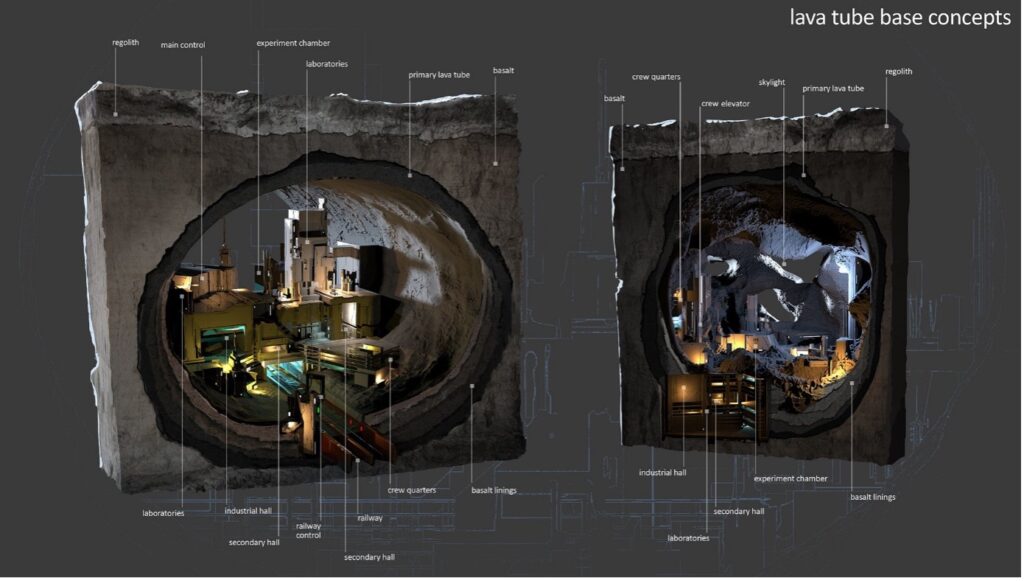

Several options have been studied to counteract these effects. One option is to use ancient lava tunnels just below the Moon’s surface to build a protected environment, shielded from external conditions (see illustration below). However, the Artemis programme is now planning to settle near the lunar south pole, where there is currently no evidence of these vast underground tunnels.

A new space industry in the making

The lunar base projects envisage surface activities, which therefore need to take into account these particular lunar conditions. In 2016, the European Space Agency presented its “Moon village” concept. The idea was to launch inflatable modules onto the surface, which robots would cover with a thick layer of concrete developed on site from lunar regolith.

Inflatable structures are not new to the space sector. An inflatable module called BEAM (Bigelow Expandable Activity Module) was even tested and installed on the International Space Station in 2016. The French start-up Spartan Space is developing an inflatable and mobile habitat solution that can be used as a temporary base camp during expeditions far from the main base.

Europe’s lunar village also relies on the massive use of 3D printing robots that can harvest lunar regolith, mix it with various glues and then spray the resulting paste onto inflatable modules to build the protective layer that will keep astronauts safe.

Because the robotics industry will have a very important role to play on the Moon. In a place where even the smallest step is a deadly risk, it is likely that robots will be used for many surface activities. But there are still many problems to be solved before we can deploy flotillas of agile and efficient lunar robots.

Between the electrostatic and highly abrasive lunar dust that gets into all the gears and sticks to all the surfaces, and the impossibility of using conventional lubricants that dry out or evaporate in the vacuum of space, there is still a lot of progress to be made and innovations to be found.

The robotics industry will have a very important role to play on the Moon.

Another fundamental point is the power supply. The advantage for the Artemis project is that the Sun is always present, low on the horizon, so that large quantities of solar panels can be deployed on the exposed sides of craters. But as the base grows, it will certainly need to be supplemented by small, compact nuclear power plants. In June 2022, NASA and the Department of Energy (DoE) selected just three proposals for nuclear fission power systems: the latter could be ready to launch by the end of the decade for a demonstration on the Moon.

But what could consume so much energy?

Mining, for example, which is one of the reasons for humans returning to the Moon. The main resource is water, of course, which is found in large quantities in the form of ice at the bottom of craters in the lunar poles. This water will be used for food and local agriculture, as well as to make fuel (in the form of oxygen and liquid hydrogen) for the rockets that will take off from the Moon.

But the lunar soil is potentially rich in other resources of immediate interest to the mining industry, such as oxygen and silicon, which are present in large quantities, but also various metals such as aluminium and iron. In the longer term, the lunar mining industry could be interested in Helium‑3, which is needed for future thermonuclear fusion reactor technologies.

If humans are to remain on our satellite for long periods of time, other technologies and industries will have to be developed to adapt to the lunar environment. Medicine, agriculture, and biotechnology will be crucial for the future, but all this will come later, once it has been proven that human presence in this alien environment is really possible.

Then perhaps one last industry will develop, a heavyweight that accounts for nearly 7% of the world’s GDP: tourism. Whether it is a flyover, in orbit or on the ground, for a short or long period, the Moon could become the unmissable destination of the next century…